INSEAD humanitarian research group

See profileLuk van Wassenhove

See profileInterview with our our affiliate: Luk van Wassenhove

Helping the world was a collateral advantage, so to speak

Emeritus professor Luk Van Wassenhove is known for his work on data analysis in the field of humanitarian aid, but his intentions were highly practical at first. “It was not my objective to do good. It was a great opportunity for me to learn. Still, my research groups have a very beneficial impact.” These research groups have ushered in improvements to relief supply chains in Africa, for example, but have also helped address sustainability issues. Van Wassenhove, who has not lost his interest in the world of commercial enterprise, insists that companies and NGOs have a lot to teach each other. “Working on sustainability and humanitarian issues has allowed me to get into new, challenging supply chain issues.”

Luk Van Wassenhove comes from a classic industrial engineering background. He graduated from the University of Leuven and worked on combinatorial optimization and large-scale mathematical programming at the University of Rotterdam. “In 1990, INSEAD (one of the largest graduate business schools in the world, ed.) came to get me because they wanted to strengthen their Technology & Operations Management department. In the nineties I got closer to the industry and primarily busied myself with supply chain management. Companies became European and then global, setting up supply networks. Around that time, I also got involved with the social and environmental footprint of all those global operations.”

Pain in the behind

In 2000, Red Cross Geneva asked Van Wassenhove to help redesign their supply chain. “Since then, I have worked on lots of issues related to sustainability and humanitarian operations. In the past five years, we’ve added health supply chains as well. What’s fascinating is that their objectives are entirely different than those of traditional supply chains. You have to figure out the impact, how you are going to measure it, and so on. For instance: how do mobile labs in Africa complement the infrastructure that is already in place, and how do you measure their added value? It is still a supply chain/ operations research problem, but collecting the right data and making sure you interpret them correctly is still a major pain. These organizations face significant data collection and data quality challenges, as finding a solution often requires aggregating data provided by very different stakeholders. These data are not necessarily neutral and may not have the same level of granularity, so you can’t just throw them all in a pot together and make solution soup. It’s important to translate the available data first before delving into analytics. Even then, you will always come across gaps and lacunas, which makes it a frustrating and challenging endeavor.” A large part of what our humanitarian research group does consists of setting up the supply chain systems and making organizational changes to get the desired results, Van Wassenhove explains. “We need to make sure that our model is sufficiently realistic and that the analysis and the robustness tests that we do are sound. That’s the only way to be sure that our recommendations are correct. We want to close the loop: rather than just analyzing a problem and finding an optimal solution, we also want to implement it and show that it works.”

My position has always been a practical one: this is a way to better understand the world of operations and technology, which is also very useful for companies.

Collateral advantage

Van Wassenhove’s personal motivation for engaging with these environments isn’t necessarily ideological: “Working on sustainability and humanitarian issues has allowed me to get into new and challenging supply chain issues. My objective has always been to learn and to do high-quality research, not to help the world. Helping the world was collateral damage, or a collateral advantage, so to speak. My position in the school – which is a business school – has always been a practical one: this is a way to better understand the world of operations and technology, which is also very useful for companies. Ten, twenty years before these issues became essential to companies, humanitarian organizations were already facing them. They knew how to deal with flexibility, agility and uncertainty in ways companies had no idea of. In fact, companies didn’t even know their supply chains: they had no clue as to who was delivering what, what they were buying from whom, and what the resilience or risk analysis of their supply chain would be. Companies have only started addressing these issues in the last ten years.”

Learning from NGOs

Although most people would assume it to be the other way around, Van Wassenhove insists that corporates have a lot to learn from NGOs. “One big lesson is the importance of purpose and enthusiasm, which lots of companies lack. Even in commercial sectors, the only way to get good results is to keep your people motivated and engaged. What’s more, NGOs work in circumstances that companies aren’t very comfortable with. Looking at the future, the only part of the world where demand will explode is Africa, and working there is very different from manufacturing products in Europe or the US. We can learn a lot from how NGOs have moved and operated. If companies want to be successful in those circumstances, they need to learn how to partner with others and understand local contexts and communities. In other words, they will have to incorporate social aspects into their businesses operations.” Still, NGOs have much to learn as well. “Analytics can have real added value in solving the problem that is climate change, because we have vast amounts of data on it. All this information can be used to forecast what the issues and problems of the future will be and where they will take place. Take draught, for instance, which might lead to famine or forced relocation, resulting in millions of refugees. We will be able to develop scenarios for these kinds of chain reactions, and hopefully develop prepositioning and relief plans, but that particular translation hasn’t been made yet. Working in Africa is very different from manufacturing products in Europe or the US. We can learn a lot from how NGOs have moved and operated.”

Many humanitarian organizations haven’t given a single thought to which data they need to answer which questions. ABW can help them ask intelligent questions about data.

SDG 17

In Van Wassenhove’s opinion the extremely vertical structure of many of these humanitarian organizations simply has to change. “Within the UN, the World Food Program focuses on food, UNICEF on women and children and UNHR on refugees. They call themselves sister organizations, and like you might expect of sisters, they ‘fight’ all the time. The WFP starts working on health, UNICEF starts working on supply chain management. If you go to a refugee camp, you might have all three of them coming in, doing similar things, i.e. filling the needs of beneficiaries. At the end of the day, all these vertical programs use the same infrastructure, the same logistics, the same trucks. The way they are working now can be extremely counter-productive and costly, and they will have to adopt a different approach to figure out how to improve. Data can help, by highlighting the big inefficiencies and the advantages of doing things differently in the future. SDGs are not independent. Health, education, hunger, poverty, inequality: it’s all related. If you focus too much on one SDG, you might actually influence the other SDGs negatively. SDG 17 (‘Partnership for the Goals’, red.) has tremendous potential, but it isn’t taken very seriously.”

ABW impact

You’d think professional organizations know what data they need, because they know what questions they want to ask and have answered. This isn’t always the case, says Van Wassenhove. “Many humanitarian organizations haven’t given a single thought to which data they need to answer which questions. ABW can help them ask intelligent questions about data. ‘If you had the answer to this question, how would it change your resource allocation to enhance your impact?’ Red Cross, UNICEF, WFP, and others all have data analytics groups. They collect data, they analyze data, but they don’t ask themselves this question enough. Why would Red Cross, UNICEF and WFP have their own analytics groups instead of just sharing information? Large humanitarian organizations need the same insights in data for several applications. Family planning is different from hunger, but they do have various elements in common. Why don’t the UN coordinate all these data analytics departments?” If ABW is going to partner with such large organizations, it’s going to be difficult to change them and make an impact, Van Wassenhove believes. “But there is a huge number of medium-sized NGOs that don’t have the resources to create their own source of data analytics, but still need the same things. There, data science can have an immediate, significant impact.”

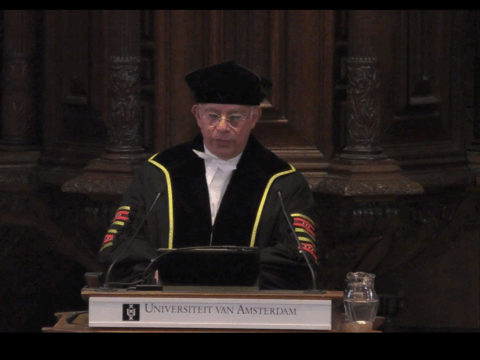

Luk Van Wassenhove is Emeritus Professor of Technology and Operations Management, as well as a management thinker and educator. At INSEAD, he holds the Henry Ford Chaired Professorship in Manufacturing. He is also the Director of the Humanitarian Research Group and a Fellow of CEDEP, the European Center for Executive Education, and a former president of the Production and Operations Management Society (POMS).

Van Wassenhove’s research and teaching are in operational excellence, supply chain management, continual improvement and learning. His recent research focus is on closed-loop supply chains (product take-back and end-of-life issues) and on disaster management (humanitarian logistics). He is the author of many teaching cases and regularly consults for major international corporations.